The role of GLUBRAN 2 cyanoacrylate glue in embolization of Endoleak

Dario Poretti MD

As we all know, endoleak treatments are probably the most difficult part of an EVAR procedure. They currently represent the majority of the complications (10-50%) after EVAR, and the main reason for reintervention (Golzarian J et al., Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2005). We mainly deal with Type II endoleaks (caused by retrograde branch flow) however also sometimes we treat Type I endoleaks, which treatment options include proximal cuff or extension endograft, as well as balloon angioplasty with large balloons (25 to 30 mm) or large stent placement. Some use coils in the aneurysmal sac and, very occasionally, we have used glue.

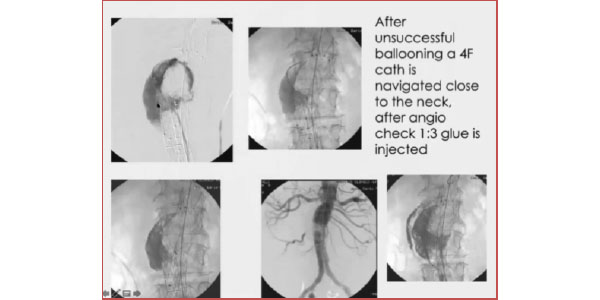

TYPE I ENDOLEAK

In this case, we had a very angulated neck, firstly treated unsuccessfully with balloons. We proceeded to insert the catheter outside the graft and inside the aneurysmal sac and checked through aggressive angiography that no flow would leak out of the sac. We injected the glue and completely froze the leak. It is a procedure that requires extreme care, but in a complex case such as this, it proved reliable. Considering hyperdensity, follow up images should preferably be taken through MR scanning, rather than CT. It is to be noted, though, that glue has less hyperdensity, compared to other embolizing materials.

TYPE II ENDOLEAK

The endoleak cavity acts as an “arteriovenous malformation nidus” thrombosing the nidus is the key for a successful embolization.

(Baum RA, Endovascular Today, 2003)

The nidus theory has been investigated: this study involved 29pts to compare outcomes of type II endoleak embolization involving: endoleak nidus only – vs – nidus and branch vessels.

Embolization of nidus and branch vessels is not superior to embolization of only the nidus in terms of occlusion of type II endoleak and change in sac size despite requiring longer procedure time and resulting in greater patient radiation exposure.

(Hyeon Yu. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017 Feb;28(2):176-184)

In terms of embolization routes, we have:

- Transarterial (leading to the nidus site);

- Direct puncture (translumbar or transabdominal):

- Transcaval (which we have never used).

In terms of embolizing materials, we consider:

- Coils

- Glue

- Onyx

TYPE II ENDOLEAK

Transarterial (case I). Navigation between graft and arterial wall

Here we have a tiny aneurysmal sac along the left side of the inferior aorta, which we decided to treat by positioning a straight graft. Before that, we preemptively close the inferior mesenteric artery with a plug, in order to prevent possible backflow or endoleak. When we found out that the sac was in conjunction with a lumbar artery, though, we first unsuccessfully tried to stop the bleeding with a balloon, then decided to navigate the catheter to reach the sac. In this case, we did not need the typical telescopic that we normally use to deliver the glue, because we had the wall of the aorta and the grafter creating sort of a sheath around the catheter so there was no risk of migration beyond the graft. We injected the glue inside the aneurysmal sac with good final results.

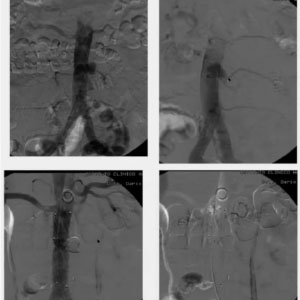

TYPE II ENDOLEAK

Transarterial (case II)

In this case, the patient developed a large endoleak after receiving a graft. Again, we decided to navigate between the limb of the graft and the artery and enter the aneurysmal sac. The angiogram revealed two lumbar arteries with no external flow so we injected the glue. The result would have been very satisfactory as we found no further endoleaks, except for the fact that I was not thorough enough to detect a vessel, so the following day the patient developed symptoms of pain in the pelvis and had an ischemic reaction of the sigmoid colon, which was treated with pneumatic dilation and took several months to resolve.

TYPE II ENDOLEAK

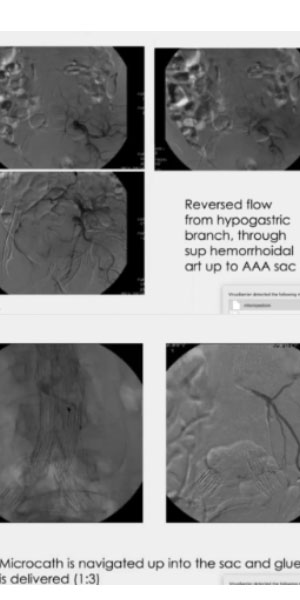

Transarterial (case III). Navigation through collateral

In this other case, we followed the endoleak flow all the way back up into the aneurysm, to deploy the glue into the sac. The injection was very careful and slow and included the first part of the inferior mesenteric artery and preserving the flow of the various branches, in order to avoid any possible ischemic complication.

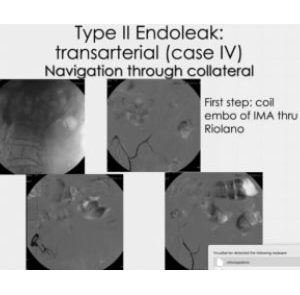

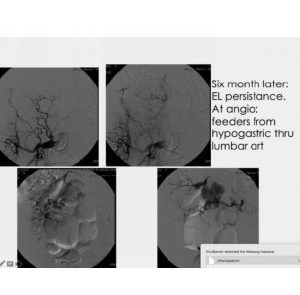

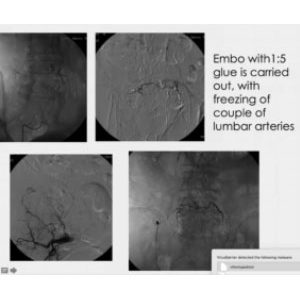

TYPE II ENDOLEAK

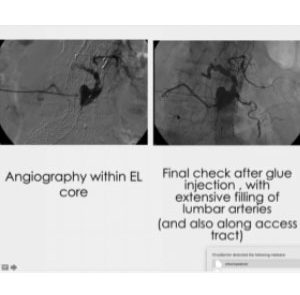

Transarterial (case IV). Navigation through collateral

Here we first opted for coils, but six months later, we realized the leak was still there. We navigated through a large network of collateral branches and injected a glue that was diluted enough to navigate even further, along the lumber arteries, close to the aorta. In this way, starting from one single spot on the right side, we were able to reach both sides, right and left.

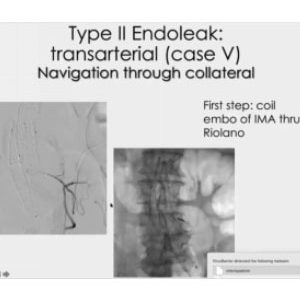

TYPE II ENDOLEAK

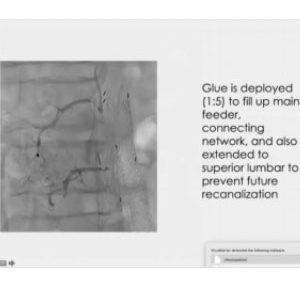

Transarterial (case V). Navigation through collateral

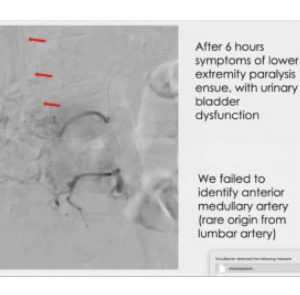

In this case, we started closing the upflow from the mesenteric artery, and later we found a collateralized lumbar artery reaching the nidus, went as close as we could, and injected a 1:5 glue mixture. I decided to push harder, in order to prevent any possible comeback. Unfortunately, I missed the anterior medullary artery. This is quite rare an occurrence, as the origin is usually around T9. The point, though, is that the mistake was not due to the glue, which performed exactly as expected.

TYPE II ENDOLEAK

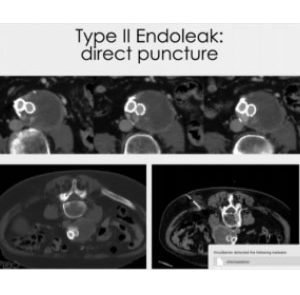

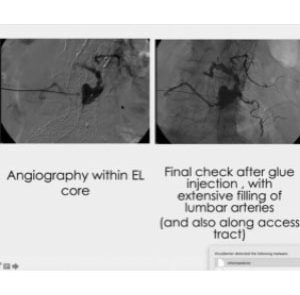

Direct puncture

The direct puncture technique requires you to aim exactly at the nidus site. If you get in the thrombus, you are not going to achieve your result. You need to insert a wire and the catheter, then, through the angiography, identify the vessels involved, control any possible risk and inject the glue, thus creating a stamp of the nidus and of the initial part of each collateral vessel. We usually leave some glue along the tract injection, in order to safeguard the walls of the aorta.